December 9, 2020

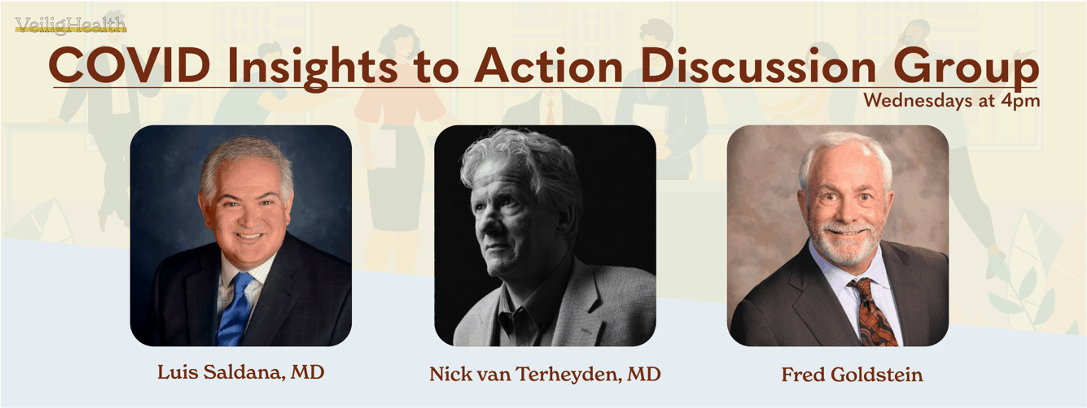

This week, Fred Goldstein, Nick van Terheyden, MD, and Luis Saldana, MD discussed the new Quarantine Guidance from the CDC, touched on the vaccines, and answered some questions from the attendees.

Transcript

Fred Goldstein 00:02

Hello, everyone, and welcome to this week’s COVID insights. This week we’ll be discussing the issue of quarantine with some new guidance from the CDC. I’m Fred Goldstein. And I’m joined today by our great group of physicians. So why don’t you please go ahead and introduce yourself start with you, Luis.

Luis Saldana 00:18

Yeah. I’m Dr. Luis Saldana , an emergency physician, current emergency room physician who’s worked also in technology and digital health as well. And, you know, all day now in all things COVID

Nick van Terheyden 00:33

I, and I’m Dr. Nick van Terheyden. I’m also an emergency room physician and focus on incremental improvements for better business, better health.

Fred Goldstein 00:42

Well, fantastic. This week, we got some new guidance from the CDC regarding quarantine, changed up some things I know, there are a lot of questions and some confusion. So perhaps dirst, we could start with what is the guidance that came out of the CDC this week? Who’d like to hit that one.

Nick van Terheyden 00:58

And why don’t I start so the CDC has issued, I guess, an updated information based on the risk profile of the disease and in particular, the potential for an individual that is suffering from COVID-19 such that the risk of them spreading infection decreases as time goes by. And the old guidance was requiring them to stay in quarantine, or isolation for 14 days, the new guidance allows for people to come out of that or not to stay in for as long without testing or 10 days. And if they’re able to test to come out at seven days. And they’re deemed to be not a risk to other people for spreading covid 19. So essentially, we’ve reduced from 14 down to 10, possibly, and even seven days. So that’s a potential halving of the period of time that people will have to spend in isolation of warranty.

Fred Goldstein 02:12

And what was the reason really, that we’re seeing for this shift?

Nick van Terheyden 02:16

Yeah, so I think the reasoning is in part driven by the challenge that everybody is having 14 days as two weeks, that’s a long time. That’s especially long in U.S. terms, given that most U.S. employees don’t even take two weeks holiday for the Europeans, they all take two weeks holiday, but here in the U.S. we don’t. So asking somebody to isolate for that extended period of time takes them out of commission, and in particular from a work or economic standpoint, so it increases challenges. And there’s also in certain circumstances depending on how people are isolating if they’re self isolating, are they using their own facilities, you know, less of a strain. But if they’re being put into quarantine, accommodation, then that takes up resources. And you’ve also got to get food to them do all of these things, that just extends the challenge. So I think it’s as much about the economic burden, balancing economics and risk appropriately with the outdated information in terms of the transmissibility of the virus over the course of time.

Fred Goldstein 03:28

And I know, Luis that when this first came out, I think there was a bit of an uproar from some providers. And so there was then sort of a pullback, what’s your sense of of that? And, and your feeling as a physician regarding the change to the guidelines?

Luis Saldana 03:44

Well, probably right. I think it probably, I would say long overdue, I think because if you think about other guidance that has been updated from the CDC, it’s a pretty long time that this went out there and has stayed out there. And the original 14 direct recommendation was based on kind of the upper bounds of the incubation. And so in other words, that was a very conservative take at that point in time. You know, early going into this pandemic, you know, really before it got to the kind of level that we’re at, that we’re at now. I think this takes a look at data, they have data that looked at and like like Nick said , also, I think you’re you’re weighing three things risk of transmission by shortening. But why would you shorten and Nick, I think explained it well, the burden economically and otherwise. And, and then compliance. I think the idea is, this will increase compliance with that, if you’re not going to be out, you know, two full weeks as far as that goes. And one thing I will point out is that these were put out by the CDC as options. In other words, they offered two additional options. A 10 day option so that is 10 days, kind of even independent of testing, which says after 10 days, you go out. The risk they did say, with that over the 14 days, you know, it seems fairly small increased risk, maybe 1%. There, there is some upper bounds up to 10%. But, but really pretty , a pretty small increase in risk. The second option is a seven day with a with a test. In other words, with a negative test. The challenge there is the logistics around scheduling the test and getting that done for that seven day period to take effect. The actually the risk profile with that, even with the negative test is still higher, they estimate about 5% increased risk as far as that goes. So, so I think you look at those and I think, you know, the different groups will take, will have different takes on this and how how they leverage this, county health departments, colleges, like we work with other, you know, their businesses, potentially, and things, but really much of it, it’s gonna be driven by whoever’s doing the contact tracing.

Nick van Terheyden 06:23

Yeah, I think it’s important to highlight that one of the risks is, as you rightly point out, Luis is, you know, these are people that are considered contacts and therefore at risk and the, you know, an assumption that they’re positive, you know, they they have COVID-19, even if it’s an asymptomatic, so how do you get that test? You know, we’re not bringing tests to those individuals, so then they have to come out, so. So there is some risk associated with testing out. And I think you’re, you know, it’s important that there are options. I, and I’m, you know, generically, I’m supportive, I think, you know, reducing the burden, and trying to increase compliance, I think is important, but where possible, I’m certainly, you know, on the conservative side of saying, you know, extend it to the full 14 days, that reduces the risk not down to zero, because there is almost no such thing, but it really diminishes as much as possible. So taking the lowest risk, or the most of the lowest possible acceptable risk in your particular circumstance, given the , the, you know, the environment that you’re in.

Luis Saldana 07:32

Yeah, and I will say one other thing quickly, is that what what’s discussed in their guidance is the PCR test. So they’re recommending a PCR test, because you’re, you know, at least, you know, you’re around seven days post exposure, potential exposure, and they feel that, in that case, the PCR test, and based on looking at numbers, they thought that is the way to really lower the risk. So I think if you did any other form of testing, you might raise that risk even more.

Nick van Terheyden 08:04

Yeah, they do actually classify or make assumptions. You know, they, they assume that the sensitivity for the antigen test was 70%. And obviously, with the PCR much higher, so it does, it raises it by about a percentage point, but they’re relatively small numbers. At the 10 day, it’s a, almost just a percentage increase if you move to antigen testing. So again, minimizing and some of this is dependent on availability, one of the things that we’re challenged with with PCR isn’t going to go to the lab, you’ve got to have the amplification process and the temperature bath and all of that the antigen testing is, you know, potentially something that might be possible to actually get to the individual and have done in situ, as it were, which, you know, while set slightly higher risk, it also means that there might be some compliance around that. So, maybe over the course of time, we might see, you know, more antigen testing as a possibility.

Fred Goldstein 09:09

And my sense of this is you have to test between day five and seven. So then the question becomes, have you gone to a place that will give you a turnaround within that period of time, or you’re just going to be in there longer, anyhow, right.

Nick van Terheyden 09:20

Right. I, I that was one of the things in fact, they actually make note of that, that you you know, the testing, you know, within 48 hours or two days of the the point in time, but taking account of delay, and I actually heard just today on the radio, the testing times have increased to three to four days and of course, that starts to diminish the value because if you’ve gone three to four days backwards. That’s no good at all. It has to be later. And ultimately, if the testing time gets long enough, you might end up spending 14 days waiting

Luis Saldana 09:54

exactly that day when you hear people’s experiences about getting their results in their PCR The it often is that. So that’d be my concern. The other concern is the logistics. Okay, so I’m in quarantine, I’m going to go drive over to the test to get my testing done. So you say, I think I’ll go stop by in the restaurant and pick up a burger. So So again, I you know, that’s why to me, it seems like the 10 day, the 10 day option seems to be the, the probably the better of the two, when you just look at all factors

Nick van Terheyden 10:30

Yeah.

Fred Goldstein 10:31

And one thing I’m not sure there’s an answer to I don’t know if either you can answer this is the way I read it, it sort of pushed it to the local public health departments as to whether or not they wanted to do that. So is it feasible that an employer group within a community says I’d like to do a 10 day with my employees and the public health department is contact tracing him for 14, you know, putting them in their quarantine for 14 days?

Luis Saldana 10:57

I think it could be depending on the like, the size of the employer, obviously, we’re working with, with colleges and colleges, I think have, you know, work with their public health department, I think what’s happening there is that they’re working with their local public health department and saying, we have the capability to do this or that or enforce the quarantine. So I think some specific some certain companies say, say healthcare companies, or hospitals and things, I think, you know, that that you can look at getting patient you have to get folks back to the workforce. And, you know, we’ve seen places in around the world where they return people to work when they’re positive. And so so you know, that we know that tested positive. So So I think, in those cases are going to be special instances where it’s not all going to be the public health department that that’s doing that they may have their own internal contact tracing and management of infection, you know, certainly hospitals have their own infection controls that usually manage all of those from from our own experience.

Nick van Terheyden 12:01

And I would say that, you know, in, in lieu of any specific guidance, I would always make the point consulting with your local, state and county regulators, being in close contact, I think people appreciate that. We’ve certainly seen that with our clients, you know, close discussions, and coordination, so that there’s no opportunity for A) misunderstandings and more importantly, for people to fall between the cracks and think that they’re complying, but they’re really not. So I would encourage that communication early and often.

Fred Goldstein 12:41

Great. Any other comments on quarantines? Or if anyone has any questions, please feel free to put them in the q&a or the chat box, and we’ll get to those. One of the things I also thought we might get to this week is we’ve obviously got some vaccines pretty close. We had a question submitted in the registration about different types of vaccines. Do you want to address a little bit that one of you, or both of you? What are the different types?

Nick van Terheyden 13:10

Um, well, so why don’t we talk about the two that? Well, there’s three, so categorize them Moderna and Pfizer are the messenger RNA virus methodology, both of which require low temperature one more so than other, the Pfizer requires us much lower temperature that requires special freezer capabilities. But they both work on the same principle of messenger RNA that induces an immune response. And then the AstraZeneca Oxford virus vaccine, which is based on an adeno virus that has been modified to produce or present the COVID-19 molecule so that the body induces a an immune response. We’ve done that type of vaccination capability with other vaccines. Pfizer is available and is being distributed in the United Kingdom went to the First Lady, I believe yesterday or the day before and the second gentleman, it’s interesting, mostly, we remember the name of the first person that in this case, I’m remembering the name of the second it was William Shakespeare, of course for Brits would no doubt pick on that. And I believe the FDA meeting is tomorrow for approval so we could start to see and I know they’ve already staged it. So those are the three. And I’m sure that we’re going to start to see more and we’ve already seen the data. I’ve seen the data on two I’ve seen the AstraZeneca data or at least the report on it and Moderna I get to i, the Pfizer I have yet to see the Moderna publication. But that’s coming up soon.

Fred Goldstein 15:08

Was there anything you saw in that Nick, that stood out different from the initial press releases that were very limited in terms of what they said?

Nick van Terheyden 15:17

No, I think they were on point. I, you know, this been a lot of focus around the AstraZeneca trial, and the fact that I think it was the Italians that got the dosing wrong and gave half doses. What I found interesting was, it seemed that that had been communicated well ahead. So it wasn’t this was a surprise, at the end of the trial, as they were sort of publishing, they had communicated that to the regulators, and had dealt with that in the ongoing assessment, and in fact, proved to be serendipitous, because it showed us that you could get a much higher, north of 90% efficacy, in the case of the lower dose in the first dose, relatively, I would say, you know, in terms of numbers, very small numbers of severe reactions, I looked at all of those, they were spread across the two arms, and in, I believe, in all the cases deemed to be not vaccine related or unlikely to be vaccine related, and there were some deaths, but these deaths were split across both arms. And they were general deaths that you would expect in a population normally, and you know, not saying death is normal. But you see that in if you grab a group of people, a large group of people, you’re going to see people dying, especially if they’re across a large age spectrum. It was predominantly cardiovascular disease that they died of, myocardial infarction . And I think it was two and two in the placebo arm and in the vaccine arm, so nothing that really jumped out. In fact, I read it and was super impressed with how much efficacy that they got. In the the two arms of the trial and side effects. The one surprise to me was there was more of the I want to say mild side effects. I don’t want to diminish how severe they can be. But you know, the flu like symptoms, sore arm, fever, aches, pains, those kind of things seem to occur more frequently in the younger age group than in the older age group, which I wasn’t expecting. But maybe that’s because our immune systems have seen so much more stuff. By the time we get to be older, that you know, we’re a little bit better able to the vaccine.

Fred Goldstein 17:46

And Luis there’s been a couple of you know, just blasted headlines recently on those two cases with in in the UK who got it with an allergic reaction. thoughts on that? Well,

Luis Saldana 17:59

yeah, I we don’t have all the specific details. But I do think Pfizer has kind of responded and said that recommending that folks that have had a history of allergic reaction to a vaccine or an employee, especially anaphylaxis, not get it as far as that goes, at least at this stage in the game. But But I wonder if he’s still candid with with kind of informed consent. As far as that goes? I’m willing to accept that that risk. I you know, I think that there’s that that’s always a risk, I think we see that in in anything that some folks are, or have a higher incidence of anaphylaxis. And, you know, I think in these cases, I even saw, maybe both of the patients were patients who carried epi pens for for anaphylaxis anyway. So so they they were already probably at higher risk. So you’re selecting a group of that? I don’t think that it’s going to be a big issue overall, I think they probably might have similar reactions to the flu vaccine may be interesting just to see if you had that data and ask them what what vaccines and had reactions to before.

Fred Goldstein 19:06

Make sense. And there’s an interesting comment in here. Really good one, actually about from Mary Beth, who says she does case investigation, and the cases are very reluctant to provide close contact information so that they can notify others and explain their quarantine requirements. We’ve sort of seen that varying rates around the country. I think there was one article that talked about 74% of people were unable to be contacted or unwilling to share cases. So any thoughts on that whole issue?

Nick van Terheyden 19:33

II would say we’ve seen that certainly in the data and the experiences with some of the clients that we’ve been working with, including a diminishing return over time, where people are less and less inclined to share information. I you know, much of this is behavioral and also a trust issue. You know, and consequences. So if I declare this, am I then you know, is there a punitive association as a result of sharing contacts did, am I perceived to have misbehaved or done something incorrectly. I mean, I think that’s, you know, if I was to sort of highlight the one approach to this, that really makes sense. It’s the same thing that we do in medicine for m&m morbidity and mortality, root cause investigation, same as the airline industry does, with zero fault approach. And, you know, I know we’re imperfect, and that we always seem to look for fault. But it’s not a fault to drive to an individual and, you know, be punitive about it, but to learn from that mistake, and we need the same thing with contact tracing. But, you know, that’s a trust issue. And we seem to have broken a lot of the trust, unfortunately.

Luis Saldana 20:47

I agree with that. With that run the trust, I think it’s also goes to something I’ve seen with folks that I’ve known that have tested positive for COVID is there’s even a reluctance to report or share that information with the folks they had. So this kind of falls really along that it’s I think they there’s kind of this sense of a stigma attached to add COVID. Like he said, some of it is, in default, kind of this kind of fault. Well, I did something wrong. And I think we really have to, to Nick said, we, eliminate that you’re not at fault here. We’re trying to, you know, the goal is for us to try and curtail the spread of this, of this virus and things. But I we definitely have heard that I think, in terms of the what, what, what Mary Beth shared, and I think we have seen it be better actually, at one of our college clients, I think they’re they’re a little more willing, now have a full disclosure, probably not, I think it’s always probably going to be partial disclosure, I did see an interesting thing I wish I had the reference to or the link to this, about doing it in a different style. And actually having folks go back and think about the you know, go back, and it’s almost like putting yourself back there and think about this and stopping kind of a very, very, it’s kind of a very different than rather than kind of a sterile approach to this. It’s a little more interactive and, and things. But right now, certainly, what are these cases, folks that are doing these case investigations that are slammed? and and you know, it’s difficult to deal with the just the sheer volume of this

Nick van Terheyden 22:40

experience and the expertise around that? It’s interesting, the contact tracing course, you know, that I went through just, you know, from an informational standpoint, a big chunk of that is about, you know, open ended questions, psychology of sort of approaching this and how you, I forget the terms, I mean, I’m certainly not an expert in that, although that’s one of the things that we try and think about in, in medicine to try and be open ended in the way that we approach it. And I want to just before we drop off, and, you know, leave the quarantine, I want to get back to that for a second and talk about sort of quarantine, you know, imagine if it’s a family member that’s getting, you know, gets a contact notification and says, hey, we’ve you know, I you You are a contact and they’re living in a shared family household. You know, one of the challenges, how do you deal with that? And I actually think you’ve got some good insights on that Fred, because you’ve essentially done that not from a contact racing, but in terms of how you go about quarantining in a sort of home setting.

Fred Goldstein 23:45

Yeah, I’ve actually had to quarantine two people in the house as they one of them when they came out of the state of New York early on and Florida was requiring 14 days. And the second when somebody left and had an exposure and had to quarantine and we said you’re going to quarantine here. So there were there were some simple things we did I mean one we were lucky we have a room, one room in the house that has a separate back door. So we had them actually come in they both actually arrived in the evening at night and they went straight into that room and the room had been already prepared. refrigerator, microwave, towels, showers, plastic bags, food popcorn, you name it, to make it reasonable and make and and then it was really about how to just ensure that they had what they need during that period of time. And we really minimize our at our access to tthem. In fact, I never saw them except once when they were outside each when they came into the backyard at that back door during the two week period. And, and the second time we made some differences because they were more issues around airflow and things like that that had become part of the bigger thing. So we looked at that as well. But you would think about if you’ve got somebody coming in your home, you may want to if they’re arriving or something like that, just clear it out, not be there. Let them get settled. Then come back in clean the place up quick. And really figure out how you’re going to get food and other things to them. I know the universities have done a lot of work on this obviously been very successful at it. So it was an interesting experience and worked well. I would like to add one point to back to the other issue is that this whole thing on contact tracing, I know Berkeley had an outbreak that they wrote about in the summer with the Frats. And they essentially recognized early on that they would not get a lot of great response from the students. And they really talked to the students about just calling the people anyhow, and telling them what they need to do. And they, they shut down an outbreak that started with about 47 people, and, and kept it from getting any bigger. And I think a lot of that was due to the students themselves self notifying who they didn’t want to make public to the contact tracers. So just something to consider when you’re doing that.

Nick van Terheyden 25:51

Yeah, I see Mary Beth talking about some of the experiences that they’ve had, and, you know, trying to make it and facilitate it as much as possible offer free at home testing, which I think is a great idea. But I think you’re right, right, that capacity to sort of provide the onward information for contact tracing, so that somebody can actually it reminds me very much of the STD slips, the paper slips that people would hand to you, it had all the information, and it was essentially anonymous, although you could tie it back to the original distribution point based on the codes on the back if you needed to, but from an action standpoint, it gave people something that they could do locally. So you know, maybe that would help from a contact tracing standpoint.

Luis Saldana 26:38

Yeah, I’ll throw one other thing, that’s certainly a huge barrier on this. And that’s the the folks that are actually are kind of essential workers are, you know, we look at the social determinants of health. The folks that live it can’t can’t, he can’t put somebody in a separate, you don’t have a separate place, everybody has to live in the same, you know, small area and things like that. So, so I think those those are challenges. And those folks certainly don’t want to kind of, they need to go to work, if they don’t go to work, they’re their, their family starves. And, you know, we know about the issue with food insecurity and, and things as well. So So I think if this whole challenge has really shined a light or shone a light on, on on these social determinants, which I think has led to the, you know, the discrepancy we’ve seen in in outcomes, the haves and the have nots. And I think, you know, I think that’s, you know, and I think that’s, that’s the factor is some, some folks just don’t can’t do what, what, what they’re asked to do, and things for, for very practical reasons.

Fred Goldstein 27:42

Yeah, that points to the need has been brought up a few times more recently about, perhaps when really, we should be doing this for those individuals who are in that situation, you know, if they’re food insecure, etc, we should be supplying that figure out a way to get the food to those folks in the house, figure out a way to help them out in that building, they’re in and deal with the issues if they’ve got a shared bathroom or something, providing them with information and resources, so they can effectively try to minimize the risk of staying in that house with somebody who’s quarantining. And I think maybe it’s something we’ll look at.

Nick van Terheyden 28:13

Before we close, I just want to quickly pick off the question from Erica, I think, you know, great point, this issue of quarantine, and isolation. You know, isolation is for a positive test. So you’ve received a COVID-19, you’ve got COVID, for all intents and purposes, in quarantine, is you’ve been in contact with somebody, but we’re not sure. And you’re absolutely right. I would even hold up my hand and say I tend to sort of blend those two terms. And they are different, they do have different meanings. We shouldn’t do that. You know, everybody from the top down, tends to use them interchangeably. If there was a positive around the CDC guidance, it’s bringing the two, quarantine and isolation durations into line because again, there was some confusion around that. But you’re right, we should be better and more on top of accuracy of terms. So thank you for highlighting that Erica.

Fred Goldstein 29:12

Yeah I’d like to thank you, too, because I was supposed to bring that up at the start of this and ask Nick to explain the difference between the two. So Erica, we really appreciate it. If you’d like to host this show next week. You’re more than welcome to do it. So is there if there any other questions out there? We’d be happy to address them. It looks like we’re coming up on the half hour mark here. We’d like to thank everyone for joining us. It’s been a pleasure. And we hope you join us again next week. We’ll let you know as soon as we can, what the topic will be and thanks again for joining us.

Nick van Terheyden 29:39

Thank you.