Joseph Webb 00:08

Health literacy is what I call the sleeping giant. We don’t know about it, but it’s hitting us is striking every angle. And we just don’t recognize a lot of the disparities in health care are really a result of health literacy. And so that trend is there and if you want to fix it, and they don’t model the problem, you got to go back and fix the cause.

Gregg Masters 00:31

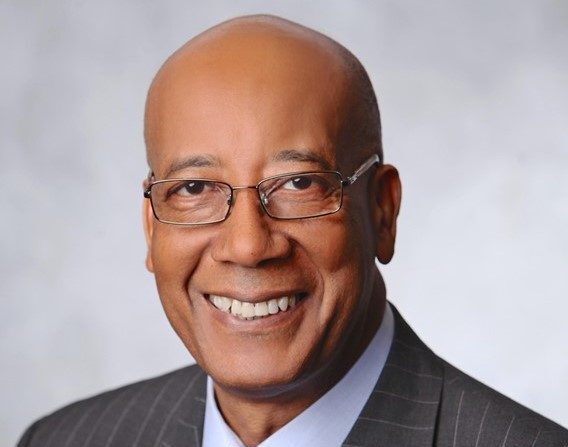

This episode of PopHealth Week is brought to you by Health Innovation Media. We create thought leadership content that supports your value proposition narrative via original or curated digital assets for omnichannel distribution and engagement via our signature pop-up studio. Connect with us at www.popupstudio.productions. Welcome, everyone. I’m Gregg Masters, Managing Director of Health Innovation Media and the producer co-host of PopHealth Week. Joining me in the virtual studio is my partner, co-founder, and principal co-host Fred Goldstein, president of Accountable Health, LLC. On today’s episode, our guest is Joseph Webb, Doctor of Science and fellow of the American College of Healthcare Executives. Dr. Webb is the CEO of Nashville General Hospital, a 150-bed academic system with more than 22 clinics and serves as the teaching hospital of the historic Meharry Medical College. Dr. Webb earned his doctorate of Science in Health Services Administration from the University of Alabama at Birmingham. And with that brief introduction, Fred, over to you.

Fred Goldstein 01:46

Thanks so much, Gregg and Dr. Webb, welcome to PopHealth Week.

Joseph Webb 01:49

Well, thank you. Pleasure being here.

Fred Goldstein 01:51

Yeah. Thanks so much for joining us. We’re looking forward to this conversation. So why don’t we start a little bit with you providing a little bit of your background and information about Nashville General Hospital itself? Okay.

Joseph Webb 02:02

My, my background, like you spent a number of years in healthcare and healthcare leadership. Actually, I began my career in behavioral health. I managed behavioral health hospitals in a for-profit system, later moved on to acute care, with the with the system out of Memphis of the Methodist Healthcare system, Methodist Le Bonheur health care system. Spent a number of years there, I’m a graduate of Tennessee State University HBCU with a Bachelor’s and a Master’s and a second Master’s from the University of Alabama at Birmingham in their healthcare administration program and a Doctorate from the University of Alabama at Birmingham in their Doctorate in Health Science, Health Administration. And so that that’s kind of my lead up to where I am now, as the CEO of Nashville General Hospital, now I’m celebrating actually at the end of this month will be exactly seven years. And so, we’ve had a we’ve had a good run here, it’s essentially been been a turnaround, I have a great team that we pulled together to, to manage that. So we have some excellent programs in place. And our mission just to get things out and into the open here as a safety net hospital, a metropolitan public hospital, Nashville. Our mission is to improve the health of the population by providing equitable access to coordinated patient-centered care. And we do that regardless of an individual’s ability to pay. And now that is a tricky equation, as you know.

Fred Goldstein 04:08

Absolutely. Absolutely. And it’s fascinating that you mentioned early on your original work was in behavioral health. I spent six years in for-profit behavioral health hospitals, running them as well. And I would assume that that allows you to look at things a little bit differently, particularly within populations you’re dealing with in Nashville.

Joseph Webb 04:26

It absolutely does. And, and honestly, I saw that in your brief description of your your background, and I said, You know what it sounds like I’m talking to myself. I’m gonna be talking to myself because, you know, once you understand behavioral health and how it impacts the overall healthcare, you know, it stated that one in three individuals will experience some form of, you know, mental health or behavioral issues, health issues during the course of their lives. And unless we know How to address that as a part of an illness and not just a something that is shone by society, that we’re not going to be effective with caring for overall population. So it’s very critical. It’s very critical aspect. And most, as you know, most hospital CEOs are really not that familiar with behavioral health, and really would rather not be still much a part of their delivery system.

Fred Goldstein 05:25

And that just gives you a unique lens, I would imagine on the overall approach that your sounds like you’re trying to do with some of these other unique programs. And could you talk a little bit about, I understand the hospitals about 150 beds, is that right?

Joseph Webb 05:36

It is licensed 150 beds, we’re not operating all of 150 of them, usually about up to 110 115, which is about what most hospitals operate in their percentage of capacity. So, so yes, we have created a couple of programs here that just to give them a quick background on why we did that, you know, the chronic care model, which I saw some of that in, in your description as well, the chronic care model, which was created at the McCall Institute by Ed Wagner, you’re probably familiar with that Michael Parchman is now the director over that he’s, Ed Wagner with his predecessor. And so the chronic care model, which we established that, and it covers the scope and the framework of how we want to deliver health care. But one thing about the chronic care model is it doesn’t provide you with all of the operational activities that you need. And so what we did was we integrated the patient-centered medical home model and patient-centered specialty practice model, NCQA model into that, because it has over about 140 elements, has six standards, and about 140 elements, which, as I was reviewing opportunities to address chronic care, I recognized that the patient-centered medical home model actually operationalizes the chronic care model, and it gives you very rigorous standards and, and structures and processes that you can put into place and actualize the the chronic care model. So that’s really what we do here, we integrate those two models, and quickly recognized that, you know, roughly 50 million or more people in this country struggle with food insecurity. So food insecurity is a very daunting task for most because, you know, it stated in the in the numbers that one in three adults in this country will experience that and will have difficulty with a certain once they reach a certain age, acquiring their medication and or food or both. So oftentimes that choice has to be made. The other piece of that is food insecurity, drives individuals to more than likely rely on food that is very non-nutritious. And we know food is medicine, we are what we eat. So if you’re prone to chronic conditions, and you’re eating foods that are high in, you know, everything, sugar, carbs, and all the stuff that you don’t need to be putting in your body is causing causing a lot of inflammation within your system, then you just go to exacerbate what is inevitable to be chronic conditions, right? Whether it’s congestive heart failure, diabetes, or hypertension. And oftentimes, you know, when individuals are categorized if you are risk stratify, and individuals are categorized in that five to 10%, that’s going to consume. And as a former CEO, you know this, they’re going to consume anywhere from 50 to 70% of your resources. And now what you have to do is you have to stratify that population. And once you can do that, then you can identify their needs, and nine times out of 10, there’s going to be a behavioral health challenge within that high-risk population. And so if you can figure out a way to address the behavioral health piece, and you can figure out a way to address the food insecurity piece, then you’re likely to be able to put that individual on a pathway to better health. So how do you how do you address that food insecurity? What we did, and this was a creation here at the hospital. I spent about 14 of my years in the Memphis market, on the board of a food bank, the MidSouth Food Bank it was tri-state, Tennessee, Arkansas and Mississippi, and they, we delivered distributed about 20 million pounds of food per year. But one thing that I never could get a really good grasp on with with delivering at that kind of capacity was making that food nutritious because you had to rely on all different sources. So fast forward that coming into this environment, I knew we needed to address an issue with food insecurity because the population that we serve being basically that disproportionately indigent population, I knew that we would have some food insecurity matters going on. And that would exacerbate the care and drive up the cost and it’s just not healthy for the patient. So the way we did this was every patient that comes into contact with the hospital to whatever entry point, ER or direct through the ambulatory division is administered a, a food insecurity assessment. Now, if what we call it, if they test positive that for that, then what we’ll do is we have that that provider will write a prescription that will go into the electronic health system for that individual to receive food from the food, food pharmacy. While there, there are registered dietitians that are in our food pharmacy, and a food pharmacy is set up kind of like a grocery store, it has aisles. There aisles of food that are low sodium, there aisles of food that are low in sugary, and carbs. And then there we have a cancer care program here. So there are foods offered that a high caloric for cancer patients. And then there’s there’s the coolers with the fresh fruits and vegetables. So the dietitian will walk the individual through to select the foods that matches up with their prescription, they get a tote bag and and they oftentimes will have family member with them. And so they’re also instructed on how to prepare certain foods and ask, then that dietitian will also give them some recipes that are available for preparing foods that they need. So so that’s how the food pharmacy work, they’re initially given 12 weeks of food. And then if you’re familiar with the chronic care model, the first item to the left of the chronic care model is community resources, our managed care portion of our ambulatory division, our LCSW works with the patient population to make sure that they are searching to find community resources that can support them, and to help them move them along socio-economically. So we try to get them transitioned off of the food pharmacy if it’s possible, but we don’t just kick them off. So that’s how that works, right. And you’ll give them a source or a resource that they can then go to, to continue to get those that food from a food bank or another group like that. And now they’re still a part of, we don’t remove them from our care management portion of our ambulatory services here. So once they are under that umbrella unless they select out, they remain a part of our population of patients.

Fred Goldstein 13:23

And so as your care management team that LCSW that you talked about continuing to follow up with them at various periods of time, depending on severity level or things like that,

Joseph Webb 13:31

oh, yes, they have regular follow up visits that are tracked and monitored. And the care management team is a part of the overall ambulatory division. So we have a number of specialty clinics, and we have primary care clinics. And so they’re there. They’re inter intra, I should say referrals going on all the time.

Fred Goldstein 13:52

And I know that you know, some of these things are a little bit hard to measure impact. But have you been able to see any sort of impact yet, in terms of measurements of individuals who are going through that program? Perhaps seeing differences in weight or or clinical status? Or just still pretty early for that?

Joseph Webb 14:09

You know? No, it’s a great question. And we have seen some, some some results our a diabetic or diabetic patients is, you know, you look at A1c, and what we’re doing is tracking A1c under control. So, you know, anywhere, I think it’s like eight, maybe eight, maybe nine under eight or nine considered as being under control. We went from 38% under control we’re at we’re at 69% under control. Now, Hypertension is a tough nut to crack and you measure the blood pressure. So for that one, it’s a little it’s less of growth, but it’s still a the incline is still going. So it’s just it’s just more difficult to manage. But we’re seeing improvement there as well. Now, let me just share this with you, our patients in the the Cancer Care Program, when we had our accreditation, triennial accreditation that that association, the group that does the accreditations for cancer programs, what they noticed was an improvement in the individual patients survival and now survivorship. And one of the things that happens with food pharmacy, which was an unintended benefit, I did not I was not aware of this when I when when we were working on putting this program together, but our patients in the cancer program oftentimes are individuals that have exhausted resources, and they’ve had to come to us for cancer, cancer care. But whether they have done that, by transferring to us, or they started with us, that still happened, and individuals that are receiving chemotherapy or other cancer care agents have to maintain a certain weight level, otherwise would have to discontinue that that treatment until they can get their weight level up. Well, what this does is, if an individual is struggling with food insecurity, then they never have to experience that because we have that component of high caloric foods that I described to you earlier, right there in the food pharmacy, so they just get a prescription to the food pharmacy. And there you go. So that’s how that works. But we saw that and that was recognized under that accreditation, and they pointed it out to us that this is an amazing accomplishment that these patients are actually showing better survivor rates, because of you know, their ability to maintain their weight and tolerate their treatment.

Gregg Masters 16:56

And if you’re just tuning into PopHealth Week, our guest is Dr. Joseph Webb, the CEO of Nashville General Hospital a 150 Bed academic system with more than 22 clinics that serves as a teaching hospital of the historic Meharry Medical College.

Fred Goldstein 17:13

That’s fantastic. That’s a great point. And some of the things that sometimes you pointed out some people don’t consider, hey, you work in fix this one, and you suddenly see this spillover effect that leads to a better outcome. Really fantastic. I know you do some other programs, too. You’ve got the I guess it’s called the CHAN program, the Congregational Health, and Education Network, what’s that?

Joseph Webb 17:32

Well, you nail that most people don’t get that name, right. But that’s exactly what it is. It is a so it is a faith-based initiative. And as you said, Congregational Health and Education Network, that is exactly what it is. We we have now, probably 110 congregations and the number continuously grows as other congregations are become aware of it. But that is basically centered around health disparities, reducing health disparities, as we know, social determinants of health, are the fundamental causes of health disparities. And when you know, the social determinants of health being items, such as food insecurity, education attainment, access to housing, access to transportation, access to health care, those are all social determinants of health. And if those are mal-distributed among populations, then you’re going to see that mal-distribution of those health disparities as well. So we know that there are certain populations of individuals who tend to rely heavily on their faith based organizations that science has shown that, particularly African Americans, and there are some other populations that do that. But so what we’ve done is we have created this network that focuses on health disparities, it is now a 501(c)(3) just recently received a fairly decent-sized grant. And so it’s it’s definitely off and running. And we focused on, obviously, we focus on health disparities, but the way we go about doing that is to attack it from an educational attainment standpoint because here’s the reason we do that, of all of those social determinants of health that I just mentioned, education attainment, is a one that will impact the others at a higher if you’re a statistics geek, R score more, or you could say, has a greater correlation than the others. And so if you improve your transportation, that doesn’t change, necessarily the other social determinants of health, but if you improve on your education attainment, then the likelihood of you being able to be at a different socioeconomic status becomes very high. And so, longitudinally, what we’re doing is working with individuals, through particular health sciences program here at the hospital, and local colleges and universities to, and we haven’t really had much, we haven’t gotten as much traction across all of them as we would like, but the system is in place that we’re moving in that direction. So educational attainment, and then there’s there’s health literacy. And then there’s access, obviously, access to health care, and supporting the faith based congregation. Those are the four pillars that fall under the the congregation Health and Education Network, we call CHIN. But the premise is this, you cannot achieve health equity until you achieve a more equitable distribution of the social determinants of health.

Fred Goldstein 21:26

Yep, absolutely. And a question on that, because most people focus on health literacy. But it sounds like you’re actually pushing for a more broader education program to get people through various levels of education. Is that part of this?

Joseph Webb 21:42

Well, interesting. That’s a good question. education attainment, based on that correlation, that strong correlation, and all science and research and all that will show that correlation, were evidence based, we’re an evidence-based healthcare delivery system. And evidence-based has always been in in the medication aspect, but evidence based has not always been in the management side of healthcare delivery. Okay. So we’re focusing on all items that we engage as tools into our delivery process, is deeply rooted in empiricism or evidence. And so yes, education will tend to change the trajectory of an individual’s life. So we can focus on that now, health literacy is a different animal. Health literacy is I don’t know, if you’re aware of there’s a tool, health literacy that is also there was also created by the McCall, McCall institute that created the chronic care model, and it works collaboratively with the chronic care model. So we have integrated that into the six standards of the chronic care model. And each standard has an element of health literacy, that it addresses. So our goal is to weave that into the chronic care model. So it’s not something we’re trying to take on independently of our overarching framework for healthcare delivery.

Fred Goldstein 23:15

Absolutely. I just thought it was fascinating when you talked about education because what I was getting at in a sense is your programs helping people stay in school or continue their education and focus on that through this through the CHIN network.

Joseph Webb 23:28

We’re just starting to get traction in that area, what we’re doing is a is a workforce development component. We have one of the local healthcare systems, who has created job opportunities for individuals. In some of the health sciences studies that we provide here, we’re looking to expand the program and continue to grow it but a rad tech program, Nursing Assistant Program, and EEG program, tech program. So EKG tech program, and so those are, those are starting points of where individuals it’s amazing, because, you know, a rad tech is a two year endeavor. And a smart kid coming out of high school that hadn’t decided whether or not they want to go to college for four years, not yet, can can go into that program for in two years, they can earn 60 to $70,000, depending on their country they’re in. And that’s a pretty good living for two year education. And so that’s what we’re pushing and promoting. We have a very small group, and it’s not very diverse right now. And so we’re looking to bring on more diversity because, you know, the cost of the program could keep some people away that goes back to you know, that, that, that social determinants of health, if you can, and as I say, if you can mitigate the social determinants of the impact of the social determinants of health at the local level, you have to prepare to mitigate those social determinants of health. Because if you can’t do that, don’t expect it to come from on, high. And those are upstream. And they’re not about to flow downstream yet. But if you can mitigate the the impact of those social determinants of health, which is what we’re doing, then you can you can change the trajectory of your patient population.

Fred Goldstein 25:27

I know, I know, the audience can’t see this, but I’m smiling ear to ear listening to you. Because what you’re talking about, you know, most people say, we’re going to go solve health literacy, but you’re actually traveling, trying to solve for that and saying, Hey, we’re going to help individuals get through a two-year program, or get this other thing to help them lift up to create and solve for the social determinants of health . Fantastic. It really is great to hear you talking about that,

Joseph Webb 25:49

you know, you can be as literate as anyone else in the world, only 12% of our population is health literate, by the way, but you can be as literate as anybody. But if you don’t have the means,

Fred Goldstein 25:59

right

Joseph Webb 25:59

to access healthcare. Right. So so that that becomes it’s not I don’t mean to imply that a secondary, but I am saying that it is a it is a part of the overall process that we’re putting that we’re putting into place, the framework that we have in place, we don’t ignore it. It is very much integrated into our system.

Fred Goldstein 26:21

Well, unfortunately, we’ve got just a few seconds here, maybe about a minute left.

Joseph Webb 26:25

We’re out already

Fred Goldstein 26:26

Yeah, it’s been great. I’d love to get you back. Dr. Webb, it’s been fantastic. And talk some more about what you’re doing really quickly, what has allowed you to turn the system, what culturally wise etc or what have you done, because it sounds like you’ve made some great progress in areas,

Joseph Webb 26:42

I think the first thing you have to do is, is meet the people where they are. Hospitals, in the public hospital is always is always going to have a challenge. You know, politically, socially, economically, it’s always going to have a challenge. And we can look at that on a broader scale. And we can talk about that sometime. But it’s no different when you’re dealing with the local, you know, public hospital. And so you have to, you’re dealing with the issue of funding. And so what we’ve done here is to try to make sure that the cost of care to this large population that we serve, is minimized. Our goal here, our strategic goal is the Triple AIM. And that is the patient experience, the outcomes of patient care, and the cost per capita, we know that we’re close to 20% of the gross domestic product as a country, the cost of health care. And so we consider all of that. And what we attempt to do here is to mitigate the impact of that by making sure that our cost per capita per patient is as low as we can get it by doing things like a food pharmacy that causes that at-risk patient to not to have to drive up their costs by showing up in our ER and having to be admitted to ICU for a diabetic crisis. That was avoidable. Had we done the right things.

Fred Goldstein 28:06

I really want to thank you for coming on Dr. Webb. It’s been a pleasure to have you on PopHealth Week. We’ll have to get you back.

Joseph Webb 28:11

All right. Thank you. Happy Holidays, by the way.

Fred Goldstein 28:14

Yes happy holiday to you and back to you, Greg.

Gregg Masters 28:17

And that is the last word on today’s broadcast. I do want to thank Dr. Joseph Webb, the CEO of Nashville General Hospital for his time and insights today do follow his work on Twitter via @IamJosephWebb and @NashGenHospital respectively and on the web via www.NashvilleGeneral.org and finally, if you’re enjoying our work here at PopHealth Week, please like the show on the podcast platform of your choice and do share with your colleagues and do consider subscribing to keep up with new episodes as they’re posted. For PopHealth Week, my co-host Fred Goldstein. This is Gregg Masters saying please stay safe everyone